The Shape of Stranger Things

Which is surprisingly not "upside down"

If you’ve never seen Kurt Vonnegut’s lecture on the “Shape of Stories,” here’s a version:

And for a great walkthrough of this, please read Joe Lazer (FKA Lazauskas)’s article. It’s quite thorough and quite good:

When it comes to Stranger Things, I won’t even attempt to track its shape across its five seasons, or even across its final season, except to call out two specific trajectories.1

For the record, I love the show (as a child of the 80s myself and a fan of its cultural references, which this season alone included Arnold Schwarzenegger's homemade spear from Predator, and Ripley pulling Newt out of the nest in Aliens).

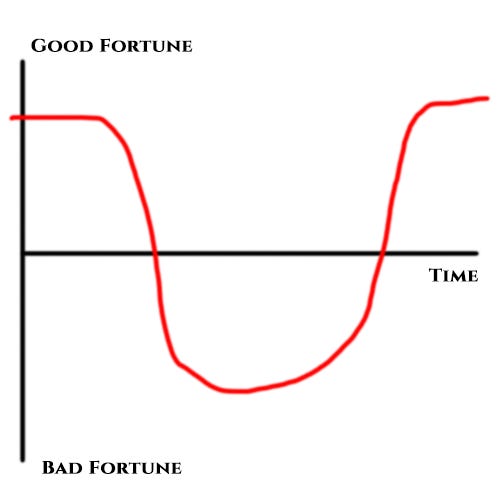

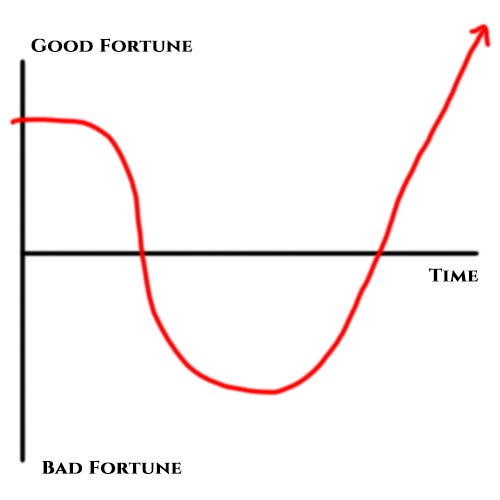

In terms of Vonnegut’s shape of stories, much of Stranger Things’ seasons follows the “Man in a Hole” model. (1). 80s kids on bikes, living a (relatively) idyllic childhood. (2) Horrific monsters bring everyone down. (3) But the kids rally together, defeat the monsters, and return to their former idyllic state.

SPOILER WARNING: Here be spoilers!

My personal complaint with this last season is that that down curve did not feel like it went sufficiently down enough. We’ve already seen the show’s monsters, so they’re just not so scary anymore, and the kids have such thick plot-armor that the demogorgons/demo-dogs never really threaten them. Vecna himself seems little more than the monster in It Follows, slowly ambling after the kids. Not to kill them, but just to recapture them in his mental prison… which is itself an idyllic setting.

Even when it came to the larger plan, the collapsing of the worlds, nothing about it felt particularly ominous or imminent. The worlds are stopped exactly where they’re needed to, in order to cross over. The threat becomes little more than a contrivance to end its own threat (the shape of a snake eating its own tail, I guess), and never started a true ticking clock about needing to save the world in time.

The other complaint is that the final upward curve goes too far up. We’ve been following these characters since 2016, we’re emotionally invested in them, sure. But to have just about all of the characters not only survive, but to return to them 18 months later to show how far they’ve continued to succeed felt a little too much to many viewers.

The “Man in a Hole” model thus became more of a “Cinderella” model, with the final curve extending up to an infinite fairy tale “happy ever after.” So much so, that people theorized that the ending was not in fact the true ending, but the kids had been captured by Vecna after all and trapped in his mental prison.

NOTE: It feels a bit like the Architect in The Matrix explaining about how his earlier attempts at creating a digital world failed because it was too idyllic. The human mind rejected it as suspect.

The Shape of 52 Pick-Up

It’s perhaps a weird complain that the characters we want to succeed all do, but not this much, somehow. And then of course, not all of them do survive—Eleven has either died or self-exiled to New Zealand (I think?) without the possibility of seeing her friends ever again.

NOTE: I will add that Mike’s theorizing that Eleven surviving is a What-If scenario that I do tend to enjoy in stories. The Lady or the Tiger—Eleven might have died, she might still be alive; I appreciate the option to consider both. Likewise, I’m good with the theory that the kids may have succeeded, or may be trapped in Vecna’s mind, without confirming either way. I love the end of Inception for the same reason.

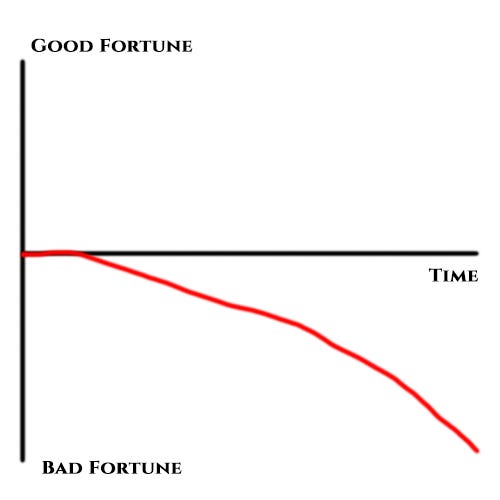

All of which said, there are other story shapes I’m even less a fan of, notably “From Bad to Worse.” Wherever the character starts, their path just keeps on going down.

I recently watched 52 Pick-Up, the 1986 thriller starring Roy Scheider and Ann-Margret. Roy’s character (Harry Mitchell) is having an affair, gets blackmailed over it, and faces increasing setbacks trying to work his way back out. Spoiler: in the end, he kills the blackmailer and rescues his wife. A “Man in the Hole” story.

What I hate about this story is its arc for Ann-Margret/Barbara Mitchell. She starts the movie in a relatively great place, nominated for a city council position, highly respected, a wealthy lifestyle. She knows her husband is a cheater (the bad), but once the story unfolds, she is continually threatened, assaulted, and degraded by the blackmailer (the worse). Harry may have “saved the day” in his story (or at least his day), but Barbara is left absolutely broken. As a viewer, I found it sickening.

It’s the same issue I have with other films similar to a Cape Fear model. The protagonist is brought low by his antagonist, only to triumph against them in the end. My problem is that bringing the protagonist low often means targeting his family—and as emotional pawns, they’re brought low and yet rarely have their own opportunities or agency to rise back up.

The Shape of the Lord of the Rings

As a counter example, let’s look at the ending of The Lord of the Rings movies. Not the books, with the rather lengthy Scouring of the Shire. Rather, in the movies we see our protagonists survive the fight, but unlike in Stranger Things, their individual stories are not all “happily ever after” with an infinite rise at the end.

Samwise may have this arc, and we’re glad for it (may he and Rosie have a happy life together). Aragon becomes king. Gimli and Legolas return to their people, but remain lifelong friends. They rise past where they started.

But other characters do not get back there. Frodo in particular (the Eleven counterpart here) never recovers from his trials. He sails to “the west” in a sort of afterlife, along with Gandalf and Elrond.

NOTE: Frodo’s sacrifice—to self-exile—at this point in the story feels earned and understood. Part of the challenge with Eleven is that hers feels somewhat akin to The Green Mile, where John Coffey conveniently chooses to sacrifice himself because he’s grown too tired to go on. It helps the plot as much as it feels like a character choice.2

As I write this, I suppose the more parallels I do see between Stranger Things and The Lord of the Rings (not just with New Zealand). Both have characters that survive the seeming impossible and come out rewarded with a personalized “happily ever after”—except for a few key protagonists who have grown too weary for this world and leave it in one way or another.

But perhaps The Lord of the Rings feels more satisfying in this regard because the lows feel truly low, and the threat of Sauron and the Ring truly impossible to overcome.

In either case, I suppose what I’m advocating for in storytelling:

Not all characters need a “happily ever after” ending. Some should get one, some should not.

The ultimate rise of a character at the end should be commensurate with the depth of their journey. A truly “happily ever after” ending has to be well earned.

No protagonist should find success at the end at the cost of their allies. Otherwise, their success feels “corrupt” and hard for an audience to value.

Sacrifices should be meaningful and emotionally charged, not merely convenient to the plot.

Bolted to the Bone

When it comes to my own book, I’ll only add (without venturing too far into spoilers) that I attempted to conclude the storylines for most characters in a mixed state—some elements of where they land at the end are for the better, some for the worse. And I suppose, some remain to be seen as I work on the next book in the series.

Also noting, that I am extremely fortunate and excited to have Bolted to the Bone be part of this year’s #SPFBO (Self-Published Fantasy Blog-Off). You can follow along right here.

Bolted to the Bone is on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Apple Books, Google Play, and Kobo. Currently at 4.32 on Goodreads!

Never mind my scribbles; if you want to see some truly beautiful renditions of these shapes, see Maya Eilam’s graphic designs.

Not an original thought, but from online discussions.

Great analysis although I had to shield my eyes because I haven’t watched the last couple seasons of ST!