Last time, we discussed the use of “operators” in fiction. Defined as a communications officer of sorts who sits behind the scenes of the action, able to help guide our protagonist through electronic surveillance.

Now let’s look at using operators in TTRPGs.

When it comes to “communications” technology in fantasy milieus1 (to borrow a certain Gygaxian term), mundane communication is not immediate over distance. Messages need physically couriers, whether runners, riders, or (GOT-style) ravens.

All of which adds its own intrigue and challenges to see if a message can even be safely delivered. So here, the fantasy messenger becomes far more of a compelling character in their own right (especially as compared to an operator), and delivering the message an adventure unto itself.

(It’s another “Old Man Yells at Cloud”-style note, so far as how storytelling tension that could be more easily built in movies before cell phones and near-perfect, instantaneous communication between characters.)

Immediate communication over distance in fantasy requires some form of “magic”, so let’s consider two means:

Scrying

Prayer

Scrying

Scrying uses various magic devices; with the D&D spell of that name, these include crystal balls, silver mirrors, and holy water. As GM, you might facilitate some sort of scrying network for the players to communicate with an NPC contact in much the same way as an “operator”. Said contact can provide needed information, warnings, or whatever rumors, hints, or clues help move the game along.

As one option (discussed when it came to mysterious strangers), what would happen if the players capture a scrying device that an “off-screen” Big Bad has been using to contact their own forces or spy on the players. Could the players use this to their advantage, sending back false information? This could provide the bards and other tricksters the chance to make use of Deception, Performance, Persuasion, and other such skills. Besides, aren’t they always looking for a good excuse to use that disguise kit, after all?

Alternatively, what if the enemy knows it’s the players, but for whatever reason cannot close off the line of communication. In essence, you might play them as an “unreliable operator” who possesses knowledge and advice, but which the players must then constantly assess (through Perception checks, various spells, etc.). This could make for an interesting guide with a memorable personality (in much the same way that mis-aligned intelligent swords often stand out as well).

Prayer

When it comes to clerics, paladins, or even warlocks, operators may already be in place as their very deities.

Going back to 1e Dungeons & Dragons, the Dungeon Master’s Guide states:

“It is well known to all experienced players that clerics, unlike magic-users, have their spells bestowed upon them by their respective deities… Cleric spells of the third, fourth, and fifth level are obtained through the aid of supernatural servants of the cleric’s deity… Cleric spells of the sixth and seventh level are granted by direct communication with the deity itself.”

Given the ongoing communion a cleric (or similar class) has with their deity, the deity or their supernatural servant (angel, planetar, archon or the like) might similarly act in the role of “operator”. Beyond granting spells, they may provide a regular guiding voice.

The Techno-Priest

While a cleric may commune with their deity through “meditation and prayer” alone, I’m also drawn to the aesthetics of more sci-fictiony techno-priests: Warhammer 40k, Trench Crusade, maybe even throwing in something of Hellraiser into the mix.

In this case, the priest may need to carry around a physical “receiver” to commune with their deity. Not merely a metaphoric one, such as how Raiders of the Lost Ark refers to the Ark of the Covenants (using Beloq’s quote in this article’s subtitle), but an actual, mechanical device2.

Much like the added challenge of operators in storytelling needing to contend with dead zones and the like, the same could be true of techno-priests. They may need to maintain an antenna with a clear signal to the heavens above, and unwind a line that’s anchored to the surface whenever they venture belowground into a dungeon.

Keeping that line open may be the only way to continue receiving spells, a precious resource and now a tactical challenge to maintain (somewhat like the comm line they needed to connect in Star Wars: Rogue One). What if the line is severed… or hauled back?

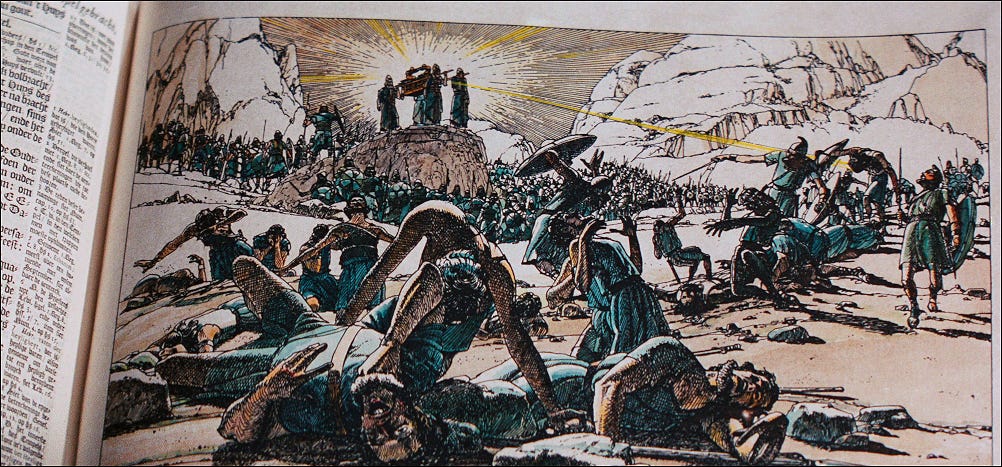

However, much like a military operator, if a tecno-priest can reach the final encounter (which may be their main goal all along) with a fiendish demon or devil of much greater power than the players, they may be able to call in an “air strike”—a divine smiting, sent direct from their deity. As a model, look at the sunbeam angled into the dungeon at the end of Legend3.

Machine of Lum the Mad

Alternatively, a transmitter may be an immovable object; a mechanical altar or even massive pipe organ of sorts, stationed within a deity’s temple. Like D&D’s Machine of Lum the Mad, this may be a profoundly advanced and complicated artifact.

Players may not even know how to operate the Machine at first. They may need to find and collect scattered “prayers”—programming codes lost to the wild; but which, when entered in the proper sequence, open a communications channel with one or even more deities4.

Find the right sequence, and players may be rewarded with learning new and more advanced spells (another way to explain the mechanics of level advancement in a more narrative way, such as how we talked about warforged regaining old memories).

Of course, an incorrect code may result in psychic feedback, risking madness of some kind, contact with a hostile (and potentially mind-controlling) entity, or incurring the wrath of a deity that’s been unduly disturbed!5

A “milieu” is defined as “the physical or social setting in which something occurs or develops”. From the French, with a literal translation of "middle place” (mi + lieu). Which is the same “lieu” in the phrase “in lieu of”, meaning “in place of”.

Fun fact about the government agents that visit Dr. Jones to set up the quest. Major Eaton (the fellow with the pipe) was played by William Hootkins—who also played Porkins in Star Wars: A New Hope, and Eckhardt in 1989’s Batman!

My introduction to fantasy literature came with a lone chapter of The Hobbit (“Riddles in the Dark”) included in a grade school reading book. An equally important exposure to fantasy film, however, came when a middle school teacher let us watch Legend for several class days in a row. In hindsight, she… may not have been overly invested in us as kids. But that movie still holds a special place in my personal canon.

Collecting components for the Machine of Lum the Mad was a major plot point in a D&D adventure I designed for Extra Life, duly named Infernal Machine Rebuild. As part of it, the player community contributed over 100 different major and minor effects the Machine could produce.

For some added recommendations, check out

(and his Raiders of the Lost Ark article/podcast—with three actual historians!).