Following our look at G.I. Joe’s Breaker, we dive into character specifics. This time, the trope of the “operator”…

The operator: a communications officer of sorts who sits behind the scenes of the action, able to help guide our protagonist through electronic surveillance.1

Think of Luther (Ving Rhames) in the Mission: Impossible series, Reaper (Russel Crowe) in Land of Bad, and of course the operators in The Matrix.

In military and espionage stories, this is someone with “eyes on the situation”, a near-omniscient (at least in terms of immediate, on-site action) observer owing to their use of overheard drones, hacked security networks, and the like. In sci-fi, this is Tank or Cypher sitting in the “real-world”, able to look at the code of the Matrix which our heroes are moving through.

The Role of the Operator

In storytelling terms, the operator is there to announce dangers and threats to the protagonist, which heightens the tension for the audience even though these threats are not yet visible (“enemies inbound”). The operator also provides the protagonist with escape routes and paths to take, allowing the chase to never slow down for the protagonist to get his bearings or navigate dead-ends.

I’d argue, however, that while this omniscience provides a clear role for the operator, it does remove some agency from the protagonist—it’s also satisfying when our hero has to find their own path; for example, Jason Bourne tearing an exit map off the wall to navigate the American consulate (in The Bourne Identity).

(An Old Man Yells at Cloud-style note: while modern technology makes travel a lot easier, there’s likewise something to be said for the days without smartphones and Google Maps. Sure, it made for a more frustrating experience, but the risk of getting lost—and finding your own way out—made for its own kind of adventure.)

Also inherent to the role of the operator is their relationship to the protagonist. They may be trusted partners. Or, they may follow the trope of “mismatched partners”. But with the protagonist out on their own, the operator provides a further storytelling service by adding dialog to a scene that might otherwise be a more narrative play-by-play of the action.

As a character, the operator often tends to be defined by the degree of usefulness in the information they provide than by any actual characterization. You might find ways to help them stand out, though, either through how they provide their information, or to give them actions beyond their operator’s chair.

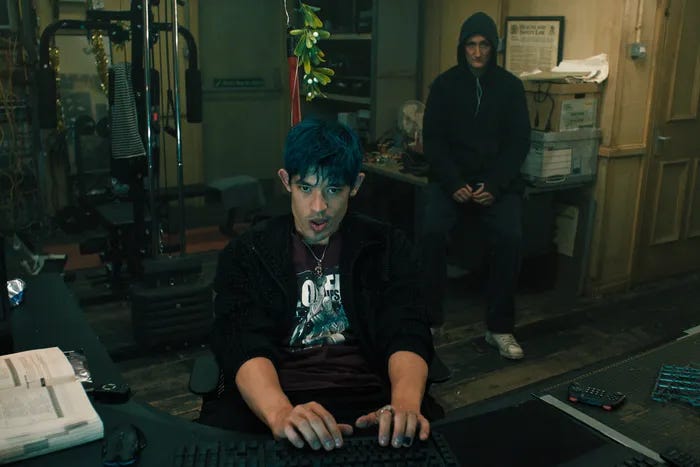

For example, in the British espionage series Slow Horses, Roddy stands out as the team’s operator both for his distinct personality (arrogant) and for how he delivers information (transactionally, despite being part of the team), as well as leaving his chair on occasion to go into the field.

Imperfect Operators

Not all operators need by omniscient, infallible, or even friendly for that matter. Our heroes need challenges around every turn! And so, some twists to the operator trope to explore include:

Greater Fog of War:

Allow the operator to have more blind spots, so that the protagonist is not able to be fully guided by them. Alleys without cameras, times when a drone can’t be overhead, etc. Don’t give your hero easy omniscience when they need it most, but always add more obstacles to challenge them more.

The Enemy Operator:

The chase may be told from the other side’s POV (which often happens when it’s the protagonist being chased by police). This may be entirely from the pursuers’ POV, or the protagonist may be listening to their operators, adjusting their own route accordingly (for a brilliant look at this, watch the opening sequence of Drive).

Dueling Operators:

Combining the two, how might it work with two operators navigating the same scene? Are they aware of one another (or even able to hear one another), and playing a version of “speed chess” with their moves? Are they instead targeting the surveillance tools of the other (a drone vs. drone duel)?

The Tricked Operator:

While unintended in this case, what happens when the operator’s dependence on their surveillance tools is compromised, and they unknowingly feed false information to the protagonist (somewhat akin to The Dark Knight, with the Joker switching hostages and terrorists, to confuse the police’s perspective).

The Unreliable Operator:

There’s also being intentionally unreliable. How might it work for the protagonist, dependent on their operator, to be led into a trap? We’ve seen this with Cypher in The Matrix. And for a series like Mission: Impossible, with its twists and disguises, what if an enemy agent were impersonating Luther? Suddenly, the hero must start trusting their own senses, rather than being what’s fed to them.

In sci-fi settings, where soldiers may wear full body armor with optics, what if an operator reprograms their feed to see things differently? Or to keep certain elements invisible (such as in 3 Body Problem)?2 What if they project the heroes as the antagonists to the rest of their allies?

Take the book Ender’s Game. What the young recruits believe to be a digitally simulated training exercise turns out to be an actual mission against an alien enemy, which Ender only learns after the fact (and after having destroyed the aliens’ home world).3

The Bumbling Operator:

Finally, what if the operator simply sucks at their job? The comically bad operator can unintentionally paint the hero into unexpected corners. And the dialog between the two can carry a great deal more frustration—and humor—as a result.

C-3PO may have access to the Death Star’s layout, but the tension is heightened because he gets overwhelmed and frustrated trying to shut down the right trash compactors.

Next time: Operators in TTRPGs.

The role of operator derives from the old telephone switchboard operators (which in turn derives from old telegraph operators), who had to manually put connect calls. Which could make for a fun mix of older technology in future settings (one of my favorites, used throughout the John Wick’s worldbuilding), if the protagonist must negotiate with an (at least initially unhelpful) operator to get the information they need.

In Dune, there’s a lucrative monopoly by the Spacing Guild and their use of Guild Navigators to manage interstellar flight. Similarly, I can imagine a sci-fi guild that’s managed to invent some ansible (or FTL) communication method. Soldiers of whatever faction must negotiate through the guild’s operators to send important messages.

Great piece and huge thanks for the mention, Bart!